Personal History of Louis Rosen (nee Rogozinsky)

This personal history was recorded by Arnold Rosen who interviewed his father Louis around 1977. It was originally posted on his own Web site at www.rosenfamilycentral.com, and is reprinted here with his permission

OLINKA

The town that I was born in was named Olinka, which around the turn of the century was part of Russia, located near the German border. It was situated three Russian miles from Grodna, the nearest large city in the area. My parents were running a small grocery business and they used to travel to Grodna to do their buying. When I was about seven or eight, my father used to take me with him to do his shopping and I considered it a tremendous treat to cross the River Niemen into Grodna. To me it was a marvelous city. Actually, it wasn't anything to rave about.

In Olinka we lived in a house facing the village square. In front of the square were the better homes for the town officials: the priest of the Russian Church, the teacher and principal of the Russian school. On one side of the square was the church and on the other the synagogue where we used to pray. Once a year, during spring, we had a fair where itinerant merchants would set up their wagonloads of merchandise. That was a big day for me because one of the wagons sold a special kind of cake for a groshen or a penny apiece. Our street was not paved. In the winter it was very cold and full of snow; in the spring it was muddy and in the summer it was sandy. I didn't mind that.

There were probably 400 people in Olinka, mostly Jewish, about 100 families. There was no "upper crust" in that town because there were lots of poor Jews, mostly peddlers, scrounging around the countryside trying to make a buck, a ruble. We had only one man who might be called upper crust. He was looked up to by some, but despised by most of the old timers because he wore a hat, shirt and tie. He subscribed to the Jewish Daily and he was called "der Deutsch" or "the German," a sneering term. He operated a business and had the only dry goods store in the town, a miniature department store. His son didn't want to go to cheder so he had a private tutor and wound up in the gymnasia or public high school. He wore a uniform and talked Russian. This family was our next door neighbor, but they were aloof. We had nothing to do with them.

The house in Olinka that I lived in was built of logs and there were shingles on the roof. Most of the houses in the town had thatched roofs. The ban in back of our house had a thatched roof. On the left side of the house was a store where we kept and sold groceries. On the right side was the living area - a front room, a dining room and a large kitchen with a stove and built-in oven. It was a big Russian-type oven. It had a little opening, like an entrance to a cave, over the top of the oven. You could crawl in and take a nap. My grandfather and I used to take siestas on top of the oven. I used to love to do that. There were a couple of bedrooms on both sides of the kitchen, an outhouse in the yard and a barn where we kept a cow and a horse. The floor of the house was made of clay or mud, packed down hard. We used to cover it with fine, yellow sand. Every so often we'd sweep out the old sand and dirt with a "besom" made out of twigs and cover the floor with fresh yellow sand. For furniture we had chairs, tables, chests of drawers and benches. The beds had mattresses made out of packed straw, but the coverings were composed of down feathers. In wintertime it could be cold, especially far from the oven. But the house was very well insulated. Between the logs, in the chinks, there was always packed moss or some such material.

There was no electricity. We had kerosene lamps most of the time. We also had candles, but they were lighted only on Friday night. On Saturday night only one candle, the havdolah candle, was lighted. We drew water out of a well on the square. The well was called a "brunnem." It had a bucket and pulley, and everybody drew their water from it. In early fall, the peasants used to bring loads of wood into the square. Whoever needed it would go and haggle with the peasant and buy a load of wood. It would all be cut up and ready for the oven.

Although we lived near them, I didn't have any contact with the town officials. We had a policeman, an officer, who would be drunk most of the time. He'd walk around in his uniform with a saber and everyone would kowtow to him.

My earliest memory probably occurred when I was about four. I recall being picked up off a muddy street after being run over by a horse and wagon. Somebody picked me up and brought me into my parent's store. Then they put a wet pack on my face. I must have been bruised pretty badly. I still carry a broken nose as a result of that accident.

About that same time I remember being brought into the cheder by my father. They made a big to-do about showing me the aleph-beth. They gave me "ruhzhinkes and mondle," raisins and almonds. If you learn well, you will eat ruhzhinkes and mondle. Cheder was a terrible drudge. I would be brought there early in the morning and I'd be confined in a big room with other kids until dark. It gets monotonous might fast, but we all endured it. That's the life kids led in the village. The rebbe was not modern. He would wield the stick if you irritated him in the least. He didn't mind if he whipped you.

The rebbe in the school was the teacher, a melamed. The spiritual leader of the village was the "Ruv," the Rabbi. I remember him as an aged person with what they call a "hadtlass punim," an imposing face with a long, flowing white beard. He was constantly at the books. He wasn't like the modern Rabbi. I only heard him make a sermon on Yom Kippur Eve. He was a very important person. As soon as he arrived in the shul, the davening would start. The Rabbi was seated right next to the oren kodesh on the mizrach, or eastern, wall. Only important people in the village had seats near the Rabbi. Anyone who had a seat adjoining the eastern wall was somebody. To sit there one had to be wealthy or well educated or elderly, or better yet, a combination of all three.

The Jews of Olinka naturally spoke Yiddish. Even thought the town was part of Russia, the gentiles of the area mostly spoke Polish, a few Lithuanian. My father was fluent in Polish, but I only learned a smattering of the language that I quickly forgot when I started learning English. As I learned English, I forgot the Polish. At one time an order came down that all the cheder kids would have to spend some time in school learning Russian. I must have been about six. I was introduced to the class, given a Russian book, but I didn't spend much time there. Why the order was changed, I don't know. Somebody was probably paid off.

MY PARENTS AND THEIR ORIGINS

My grandfather's name - my father's father - was Yakov Dovid Rogozinsky and his wife was named Yentil. He was quite educated in Hebrew, well respected, with a seat near the eastern wall. He had what they called a "zocher," which was the privilege of davening shachres every holiday. That was his chore or honor, whichever way you look on it. He considered it a great honor. It would have hurt him terribly if her were denied that privilege. He was very active in the shul, gathering funds for "moyess chitim" or relief for the poor, so that they may have wine, matzohs, provisions for Passover.

My grandfather was a smithy; he was the village blacksmith. While no one was wealthy in this little town, this trade made him better off than most. The peasants used to come to him to have their wagons repaired and their horses shod. He was always busy and made a living that way. Although my father was raised in that type of work, he drifted away from it and became a storekeeper. He engaged in all sorts of ventures. He ran a dairy, bought and sold grain from the peasants, gave contracts for selling other provisions. I don't know if he made much money, although he must have made something. But my grandfather was as I have said, quite educated.

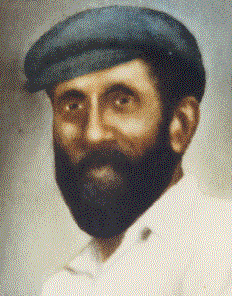

Moses Rogozinsky

1870-1948

My father carried through his life a deformity of his right hand that was self-inflicted. When he was reaching military age, I imagine around age 18, he cut and severed the tendon of his right trigger finger and bandaged it in a bent position so that when it healed, he could never straighten that finger out. It wasn't an uncommon practice for young men to mutilate themselves. Military service in the Russian Army was something that the average Jew dreaded because it was anti-Semitic to start with and the time of their servitude was long. They would have to forget about their faith as far as upholding the dietary laws and other aspects of religious life. A lot of them who didn't want to serve did anything they could to avoid it. When my father was called for service, he showed the officers his hand and told them that the finger would not straighten out. They didn't believe his story, so they had him lay his hand down on the table and pounded it with their fists to try to straighten it out. They didn't succeed. They hurt it, but that finger never did straighten out. For the rest of his life that finger was bent.

Sarah Meretsky

1870-1948

My mother was the oldest daughter of her parents. She lived in Shtabin with her mother. Her father had been in America for many years. His name was Avrum Mayer Meretsky. Meretsky was my mother's maiden name. He had gone to America with his two sons and a daughter. His wife, my grandmother, couldn't go because she was sick, and my mother stayed with her and took care of her. My Uncle Hersh, who was in Shtabin, introduced my father to my mother and they decided to make a shiddoch, a match. She was supposed to have been an heiress because she had a father in America and every man in America was a millionaire! Well, it turned out he wasn't a millionaire. He was far from it. He was making a poor living as a tailor and presser in a second-hand store and pawnshop on Michigan Avenue in Detroit. He worked for the same man for 50 years and lived to a ripe old age.

My mother grew up with little contact with her father. He had come to this country with his other children and watched them grow up. He was closer to them. When he left for America, my mother was a small child and she didn't see him again until she came to America, except on one occasion. He did come back to attend my parents' wedding and pay the "nadon," or dowry. Then he went back and didn't see her for many years. So there wasn't that closeness of a father and daughter, as there was to the other children who grew up under his nose. I remember meeting him when we came to this country. He was living at that time with his fifth wife, having buried tow and divorced two! He lived to be about 90. He was a beautiful looking man. So was my other grandfather. Both had beautiful physiques.

Most of the Jewish people in the town were religious. But our customs did not dictate that married women should shave their head or wear a "sheitle," and my mother did not wear one. A few did, but they were the exception. My mother met my father through a match arranged by my uncle. They didn't exactly meet on their wedding day, but they had no courtship like in modern times. Even so, they go along pretty good. And if not, there were no divorces then. You hardly ever heard of them.

My mother was a very pleasant person. She was outgoing and made friends easily. She was bright, in her ways. She wasn't educated, but she was smart. My father on the other hand was smart in a lot of ways and "other worldly" in some ways. He was very religious but quite tolerant. When I returned from my Yeshiva studies in New York, I told him that I didn't want to lay tefillin any more and daven every day. I know it hurt him terribly. He shrugged his shoulders and said, "Well, you're past your Bar Mitzvah, and it's your decision." I loved him but we could never see eye to eye because he was very religious and I was respectful but not observant. My father, seen from the present day, would seem a fanatic. He believed the Messiah would come riding on an ass. To his dying day he believed it. He loved Israel but said maybe that's the way the Messiah wants it so he can return among his own kind of people.

I think my parents were good parents. They showed no favoritism. His children were all different, and he loved them all. I think he was proudest of his youngest son, Nathan. My mother loved all of us with a deep love. Why she could have given her last, her life, for any of us. You could always count on my mother being accepting, spreading a table for anybody that came to the house. They never regretted coming to America. Maybe deep down my father wished he had never left the old country. But his children grew up here and he took pride in them.

I knew some of my mother's family, the Meretskys. My mother's brother, Shmuel Meretsky, lived in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and had a soft drink manufacturing business. Another uncle, Abe Meretsky, lived in Detroit and was a junk dealer. My aunt Mirke Meretsky married an Isenberg and they also were in the junk business in Pontiac, Michigan. I visited with Aunt Mirke, who lived in Detroit at the time I did. My family was living in Battle Creek at the time, but I was left behind to study to become a rabbi.

My father had two brothers and three sisters. He was the youngest. After my father got married, his oldest brother, my Uncle Max, and his wife came to Olinka to say goodbye to my grandfather. My father then took them across the "grenitz," or border, to Germany. That's where they had to go to board a ship for America. They stole across the border. My father loaded up a wagon with hay and put them in the center of the haystack. He went across the border to sell the hay to a merchant in Germany. The soldiers examined the wagon, even stuck bayonets into the hay, but they were well concealed and got across.

THE MIGRATION TO AMERICA

My father left for America about 1907 or 1908. I must have been about seven or eight years old. Then about a year later my older sister Rosie and older brother Pete left for America. I think my mother in the rest of the children, including myself, left six months later.

When my father decided to go to America, his father-in-law sent him a ship carte, a passage to come to America. My mother wanted him to go. She complained that he wasn't sending enough money - never enough - but not about being left behind. My father was only going for a little while to make his fortune, then return a rich man. When he came here, he found that the fortune was hard to come by. Besides, my mother wrote that his brother had appropriated the house and everything else, so there was nothing to come back to. So, my father sent us a little money, and mother sold whatever she could, and we came to America. At that time there were three of us kids with her: myself, Anna and Marian (Label, Hannah and Mirke).

Before we came to America, my mother had to move out of the house that we had lived in since she got married and where she had raised her children. It seems that my father's older brother Hersh had also married a girl in the town of Shtabin. Hersh was a smithy there like his father, my grandfather, was in Olinka. Nearby another smithy came in and opened up - a gentile - and my uncle's business dwindled. So he came to Olinka without my mother's knowledge and he persuaded my grandfather to let him take over his business. My grandfather was getting old and he wasn't doing too much work anyway. One fine day my uncle showed up with two wagonloads of his furniture, his house wares and tools, and crowded into the house with himself, his wife and children. They took over the kitchen and the entire hose except for one room that was left for my mother and us kids. My father had already gone to America, and we were talking about following him there, so that's why my grandfather was influenced to do what he did. Ultimately my mother moved away and rented a little apartment in a vacant house for five of six months before we actually left for America. The whole business left a lot of bitterness between my mother and her brother-in-law and her father-in-law. My mother thought that my father owned the house because he had built it and the store. My grandfather thought that he had owned it all the time. Where the truth lies, I don't know. Chances are they both owned it.

I remember when we crossed the border. We went from Olinka to Yagastov, the closest town near the border. My mother had a friend there. We spent the day there and at night her friends drove us to a farmhouse close to the border, and my family - my mother and us kids - and another family hid in the barn behind the house. We spent the rest of the night there. Early in the morning, the farmer woke us up and led us to the border. Only a small river, a brook, divided the two countries, Russia from Germany (or Prussia). There was a narrow bridge and Russian soldiers were watching the crossing point, parading back and forth. Early in the morning they changed the guard, and while they were doing that, the farmer slipped us across the bridge into Germany. We came to a village in Germany and there was a wagon waiting for us to take us to a railroad depot.

I don't know what would have happened if we had been caught. I was a child and was too young to be scared. I guess my mother was frightened, but to me it was exciting. I looked forward to go to "Amerike," the golden country. I felt no regrets leaving Olinka.

We got our train tickets and traveled to Bremen. This was the first time I had seen a train, much less ridden on one. That was exciting. Bremen was a large seaport and we wound up in the immigrant house where we spent a few days waiting for a ship. I think the ocean trip took ten days. I got seasick very badly. I remained in the hold. I was deathly sick. Only on the last couple of days of the voyage did I feel well enough to come up on the deck. I hardly ate anything the whole trip. Towards the end I was able to eat dried bread. They had a special kind of dried bread that I enjoyed eating. They called it "kacharis".

I remember seeing the other immigrants. There were Italians, Jews, Russians, Germans, various nationalities. I like to watch the variety of people. We passed the New York harbor, saw the Statue of Liberty and stopped at Castle Garden or Ellis Island. This was the gateway for most immigrants. A lot of people got off the ship but we stayed on and sailed to Baltimore. When we landed there, they held us for a couple of days and my mother was terribly worried. She didn't have enough money to show, or something like that. You had to have a certain amount of money with you to show to the immigration authorities, and she didn't have quite enough. So they held us there, in a kind of detention, until she received a money order. Then they let us go.

We boarded a train and traveled to Pittsburgh, on the way to Detroit, our destination. At Pittsburgh, we had to change trains. We were very hungry - all of us - but we had to stay in the depot and wait for the train. A stranger, a Yid, came by and got into a conversation with my mother. He said, "Sure. Let him come and we'll buy some baked goods." He told her that. So, she gave me money and sent me along with that man, and she felt sorry that she allowed me to go with him, because she didn't know him, and she didn't know if I'd ever come back. Anyway, he took me to the bakery and asked what I wanted to buy. He says to me, "Du gleich das?" or "Do you like that?" We didn't have that expression, "du gleich das?" We said, "Das ist liebe," "Das ist hold." I said, "Gleich? Gleich?" He said, "Du willst das?" or "Do you want that?" I said, "Yeah!" Anything he showed me or pointed to, "Yeah!" I bought a big bag of baked goods. My mother was happy to see me come back with it. It tasted delicious!

I remember seeing in that depot two black porters, eating their lunch. I had never seen anything like them in my life. What were they, what kind of people? One of them offered me a sandwich. I refused but continued to stare. Evidently they didn't mind because they let me stay there and stare.

Well, we got to Detroit and there was my father to meet us. It was deep in winter and miserably cold. We left the depot deep in snow and frost. I almost froze. I shivered. I guess I wasn't dressed too warm. I'll never forget it. I was finally glad when my father brought us to my Aunt's house, Gudkin Meretsky, my mother's sister-in-law. She fixed us the most delicious meal I have ever eaten in my life. There were only hamburgers and potatoes, but to me it was delicious. I hadn't had a decent meal since we had boarded the ship to Bremen.

I had no trouble recognizing my father, even though I hadn't seen him for a couple of years. He was a nice looking man. He had a trim little whisker. He was a handsome man in his younger days.

RABBINICAL STUDIES AND MISFORTUNE

What happened to me after we arrived in Detroit was tragic. My father took me to the rebbe, Rabbi Levin. They had a discussion. I don't know what my father told him; I wasn't a party to it. Then the Rabbi called me in, opened up the gemorrah and said, "Read." I read pretty good. I read one line and another line. When I stumbled at the meaning of a passage, I looked at the Rashi and Tosfos, the commentaries that explained the passage, and told the Rabbi what it meant. He said, "I like that, " to my father. "The boy for his age is quite good." He says, "I'll arrange for him to stay in Detroit. I'm thinking of starting a Yeshiva, and he'll be my first pupil." So my father and the family went to Battle Creek, and I was left behind. The Rabbi arranged a place for me to stay and he arranged board for me. That was a tough life for a ten-year-old.

I stayed with a Mr. Cohen and ate every day at a different place. It was a rough life for three years. I very seldom saw my parents. They lived in Battle Creek, 120 miles from Detroit. After my Bar Mitzvah, they sent me to a Yeshiva in New York. I stayed there a year and that was it. I refused to stay any longer. I told them to send me home, I'm tired, I have no interest in learning any more, I want to go home. Even though I had been at it for three years, the older I got, the more homesick I got. I felt I wasn't cut out to be a Rabbi. By that time I was reading socialist literature and had lost any deep religious faith.

Those were terrible years. I rarely got a letter from my father. Out of sight, out of mind, more or less, with them. Now and then he'd send a few dollars, but very seldom. The Yeshiva paid for my room but I had to scrounge for food. They had a little dining room for one meal; the rest I had to buy. From age ten on, I was like an orphan. I had no home life. I had no childhood that a normal child had: no games, no play. I had too much responsibility beginning at age ten.

So at age 14 I returned home. My father had a junk shop in Detroit. While I had been away, three more children had been born: Angie, Nathan and Helen. We lived in a cottage. It wasn't a high-class home, but it was typical of those days. We didn't have electricity; we had gaslights. In the kitchen was a cook stove and we had a parlor stove for heat. We had running water with a pump in the sink.

EDUCATION, WORK AND MARRIAGE

I started high school in 1914 and graduated in 1918. My ambitions were varied at that time. I had hoped that maybe I would study medicine. Every Jewish boy wants to be a doctor, or his mother and father want him to be a doctor. I was no exception in that respect. But I couldn't see my way clear to finance myself, because at that time my folks moved out of town to Pontiac, Michigan. I joined the SATC, which was organized for high school graduates to go to college and prepare themselves to be officers in the Army. I was given food, clothes, a place to sleep and some spending money on top of that. But it didn't last too long. The Armistice came in November, and we were mustered out the following month. I went to work at different jobs and studied in night school. I took a law course. I figured that even if I don't practice law, it wouldn't hurt to have that legal course. I'm glad I did. It wasn't a sacrifice, really, because I enjoyed going to law school. And I managed to play around a bit, plenty, while doing so. I graduated the law and took the bar and passed that in 1923.

During the years between finishing high school and passing the bar, I worked in a variety of jobs, most of them as an inspector. I didn't have to operate a machine or do any dirty work. My job consisted in measuring and approving the work coming out of various machines. I got into that kind of work while I was in high school. Those were war years and there was a shortage of help in the factories. I used to go and get a job on Friday. I'd work Saturday night and Sunday night on the night shift and then I'd quit. They'd pay me time and a half for Saturday and double time for Sunday, so I'd collect a pretty good chunk of money. At the same time I learned my way around. I learned which jobs paid pretty well, what ones were nice to ask for. I found by experience that I could get a job as an inspector. I didn't have to lie that I had a pretty good education, and I knew how to handle measuring tools. Before long I learned how to handle a micrometer, how to read a scale, how to read a blueprint, etc. Gradually I gained experience, but I got fired from a couple of jobs. Once I remember they put me on a line of drilling machines, and I had to measure the size of the holes. They gave me a pair of plug gauges, what they called "go" and "no go." "Go" goes into the hole, but "no go" does not. In other words it's big enough and not too big. One of the guys says to me, "Oh, you don't have to worry about checking my machine. I'm an expert at that." I believed him and paid no attention to him, sort of goofed off. Well, he didn't drill the holes straight down; they went in on a bias. He goofed up but I was held responsible for it. So I learned by experience.

I had a good time in those years. I had friends and we'd go to places. We'd go to a dance, go out looking for girls and yes, we'd find them. We went to movies; they were a big thing in those days. I didn't have a car, didn't feel the need of one. Nowadays a young man without a car would be an oddity. In those days very few fellows had cars. There were all kinds of transit, buses and streetcars. Transportation was no problem.

I was 23 when I graduated law school and I wondered whether I should get a position, try to get tied up with a law office, or whether I should wait a while, same some money, and open a law office of my own. I had a good friend by the name of Goldstein. We went to school together. We graduated together. We both took the bar; he didn't pass. One nice day he gave me a proposition. We would open an office in partnership. His pitch was that he had a steady source of practice, that his brother was an official of Robinson-Cole, a big furniture store, which was correct. They had two stores in Detroit and Goldstein could handle a lot of business through his brother. We could have an entry into Robinson-Cole: contracts, collections, whatever. It sounded good. I knew he had to have me on account of the fact that I was a member of the bar and he wasn't. We rented an office and I invested all my money and more to equip it. He had a desk and I had a desk. He had his private office and I had mine. Well, we were there for two or three months. He was always busy, hardly ever in the office, always on the go, but nothing was coming in the office. I did a little snooping and found out that his sister was working in a downtown law office. His desk contained a couple of abstracts and a typewritten brief with the letterhead from that office. I realized that he wasn't being fair. He wasn't a partner; he was just using me as a decoy. So we parted company right there and then. I had the furniture and the office equipment, so I looked around for another office. I found one on Hastings Street where a shipping agency had just opened up. They were selling traveling tickets to come to America from different countries through various shipping lines. So I rented part of that office. It wasn't bad; I got some legal work but barely enough to make expenses. I wasn't getting rich. But even that didn't hold up because the government passed a law barring immigration, and the only passage they could sell was to Canada or to Cuba, not to the United States. So they went out of business, and I folded up with them. By that time I had been at it for a year and a half. I had gotten my belly full of it. I thought to myself "the hell with the law business; I am going back to my old work." That was the end of my law career.

I met my wife in a funny sort of way. My father had a friend I Detroit by the name of Lieberman. In the fall of 1926, Mr. Lieberman told my father that I should call a certain girl, that she would make a good match for me. Well, my father and mother pestered me to call that girl, by the name of Harriet Kotinsky. Her father owned a lot of real estate, and he had a store. The story was that he was wealthy, and that the girl had $10,000 cash to go with her upon marriage. It was a real enticing tale. I'd seen the girl once, and she wasn't bad looking. She was a nice Jewish girl. I visited at her house, spent some time with her, her father and mother. I made a date to see her again, in the afternoon of a holiday, Rosh Hashanah.

She was a good Jewish girl, and she didn't want to do anything on the holiday, so she suggested that we take a walk to her girlfriend's house, Mildred Cohn. Her friend lived on Henry Street. We went there and she introduced me to Mildred, and I was treated to strudel and coffeecake. Mildred appealed to me, right away.

So I took Harriet home and I went back to my sister Rosie's house, who was living on Medbury. I told her that I had just met a nice Jewish girl, Mildred Cohn, and I am going to call her for a date. Rosie knew about Harriet and said I was passing up a "schmalz pot." She told me it was foolish to even do a thing like that when there was such a great opportunity available. I called Mildred but she refused to see me, thinking that I was Harriet's boyfriend. I kept calling her and finally she agreed to go out with me. We often double-dated with my cousin Irving. Irving and his girlfriend decided to get married. That sounded like a good idea, so I asked Mildred. She refused, saying she wasn't ready to get married. Well, we broke up over this issue, and I didn't see her for a year. She apparently moved in the interim and when I tried to call her, I didn't have her number. I kept calling all the Cohens and Cohns in the phone book. When I finally reached her and said, "This is Louis," she said, "When did you get out of jail?" We started dating again and ended up getting married on January 1, 1928.

We went on a honeymoon to Chicago and stayed at the Morrison Hotel. It's now been thrown down. We came back to Detroit and lived with Mildred's parents for a few years, until Jerry was born. Then we moved to an apartment. My in-laws were swell people; we got along really good. There was never any friction and we didn't mind living with them. I can't recall ever getting angry with them. My wife and mother-in-law shared the kitchen, but I wasn't interested in who cooked what. All I wanted was food, and I got plenty of that. I didn't care who prepared it or how. From my in-laws', we moved to an apartment on University. Later we moved on to a flat on Pasadena.

In 1931, in the depths of the depression, my father had very bad asthma. He heard that Arizona was a good place for people with asthmatic conditions, so he loaded his family in the car and headed southwest. I'm not sure why they ended up staying in Dallas. One story I heard was that they came into Dallas on Friday and they didn't want to travel on Saturday, on Shabbos, so they stopped. My father went to the local shul, got acquainted with some of the Jewish people there, like the place and decided to stay on. Another story was that their car broke down in Dallas, they had to stop, so they wound up staying. Nathan got a job to help support the family. My mother opened up a store, a small place, little more than a doorway on Elm Street. But they made money.

After the war, Nathan called me to come down to Dallas. I came down and liked it, but Mildred didn't want to leave. She kept writing alibis that she couldn't sell the house or the furniture. But the truth was that her mother died recently and her father was living with her. She didn't want to leave her father. But he went to live with her brother Joe, and she came down to Dallas. I worked for Nathan, and then I got laid off. I saw an advertisement for a curtain laundry for sale. I contacted the owner, Mr. Ashmore, and he told me that he wanted $4500. I told him that I wasn't experienced in that line of work. I didn't know if I could make a living at it. I said, "I'm willing to take it off your hands on a lease arrangement with an option to buy. I'll pay you so much a month, and if I can see my way clear to make a living out of it, I'll buy it for $4500." We went to his lawyer and worked it out. After my wife and I came into the business, we decided the lease arrangement was too much to pay out, and that we'd be better off to buy it. We took an awful chance, but it worked out okay.