Rose and Rolf Diamant

Rose Bloom and Rudolph Diamant were married on August 31st of 1913 in New York City. Rose was my grandfather Dave's older sister, born five years prior to him in 1888, and before the family had emigrated from Goniadz, Poland in 1891. Rudolph was born in Amsterdam, and had immigrated to New York in 1909 at age 23.

Rudolph worked as a statistician for the insurance industry, but he was also a freelance reporter, having written extensively for the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant (a Dutch financial daily) on the 1909 Hudson River celebration. This event was a commemoration of the tricentennial anniversary of Henry Hudson's exploration of the river, as well as the centennial celebration of Fulton's steamboat. These dispatches were translated into English and published by Rose and Rudolph's son Lincoln (also a prolific author) nearly 100 years later.

Rose was a talented sculptor. She was close with the renowned American artist Gutzon Borglum, who is best known for the presidential portraits carved into Mt. Rushmore. The story in Rose’s diary begins in Borglum’s sculpture studio, to which Rose was given free access for her own work.

Rose was a talented sculptor. She was close with the renowned American artist Gutzon Borglum, who is best known for the presidential portraits carved into Mt. Rushmore. The story in Rose’s diary begins in Borglum’s sculpture studio, to which Rose was given free access for her own work.

In 1915, Rose and Rudolph's first child was born, a boy they named Rolph (a contraction of "Rose" and "Rudolph", which was later changed to Rolf). The young parents doted on their son, evidenced by the volumes of narrative prose and photographs exhaustively documenting Rolf’s happy first year of life. For more on this, see Rudolph’s journal, which has been scanned and reproduced online.

Tragedy struck the young family in 1917, when Rolf inhaled a piece of a walnut shell a few months before his second birthday. Such a foreign body in the airway was and remains a serious condition, but is readily managed today by an experienced otolaryngologist (also known as an ear, nose and throat physician). Removal involves the passage of a rigid tube into the airway (endoscopy), and the use of instruments that are long grasping forceps combined with illumination and telescopes, which allow for the safe removal of such objects under direct vision.

In the early twentieth century, these techniques were just being developed by the famous Philadelphia surgeon Chevalier Jackson, and had not been widely \disseminated or perfected. Prior to the general availability of this endoscopic extraction method, a foreign body in the lungs was usually a death sentence, from progressive airway obstruction, infection, or the high risk of an open chest operation.

Rolf was brought to New York City to be treated by another famous ear, nose and throat physician - Dr. Sydney Yankauer. In this diary, Rose tells the story of the days between Rolf's choking on the shell and his sad death three days later.

The medical course of Rolf's illness is not exactly clear from the text, as the story is told from the limited point of view of a parent. However, it seems that at least part of the shell was extracted endoscopically (without general anesthesia). Later, with Rolf at death's door, a temporary reprieve was obtained by the placement of a "silver tube" in his throat, most likely a tracheotomy. Although it is not clear whether he died of airway obstruction or sepsis, Rolf passed away soon after his second operation.

Rose’s diary is presented here as transcribed text for easier reading, although the original handwritten volume is available as a PDF file for download.

Reading, researching and editing this little volume has been a great personal journey for me. The re-discovery of the diary by my cousin Betsy (Rose and Rudolph's granddaughter) gave me the opportunity to work in this unique intersection of my professional world (otolaryngology) and one of my passions, genealogical research.

The diary is fascinating on two levels. For the physician, the diary is an intriguing first person account of an early world in medical history, where we recognize the shadows of our own beginnings. A surgeon reading this text is projected behind the closed doors that hid much of Rolf’s hospital course from his mother, imagining the dialogue of the consultants that Rose never heard. It is humbling and illuminating to realize how something as simple as a smile or an offhand word, dispensed without thought in the course of a busy clinical day, can mean so much to a patient or a family member.

For the lay audience, the diary is a striking reminder of the fragility of life, especially before the advent of modern medical and surgical techniques. Accidents and injuries that are now minor annoyances often ended in unspeakable tragedy.

Rose’s narrative lets the reader feel the powerful emotions of those three days. Her obvious pride at her son’s brilliance at such a young age, her deep devotion to his well being, her fears of the unknown, her brief rays of hopefulness, her worries about her husband and her crushing acceptance of the inevitable are beautifully and tragically written in her own hand.

Michael Rothschild

April, 2011

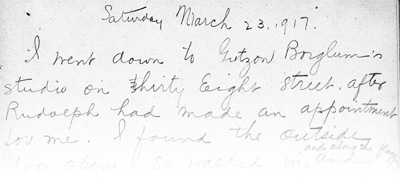

March 23, 1917

I went down to Gutzon Borglum's [1] studio on Thirty Eighth Street after Rudolph had made an appointment for me. I found the outside door open so walked in and along the flagging and met the young man who works for Mr. Borglum just coming out. He asked me what I wanted; I told him I was Mrs. Diamant, so he showed me into the studio and went right out.

I stood near the door hesitating to go further, but Mr. Borglum, who sat at his desk in the corner to the right, told me to come over and sit down. He had his blue smock on, and he seemed to light up that corner of the studio.

He asked me about my baby, and I told him of his tragic death, how he had put a piece of nut shell in his mouth and so had gotten it into his windpipe, and after three days of suffering had died. I could not help crying when I told my woeful story, but I calmed myself immediately.

Mr. Borglum was very sympathetic, told me I was still young and would have other children, but I told him that quantity would never make up for one. Most of our friends say as Mr. Borglum, but can any other children make up for that most beautiful life just snuffed out at the most promising stage of his life? He understood everything we said to him, and enjoyed everything he came in contact with, to a child's fullest measure. He loved the library with all the books, and he was in his element when we left him alone to his desires; to take books out of the bookcase, turn the leaves, pretend to read, put the book down, take another, and look for flags. He liked to see the colored flags in Rudolph's French dictionary. And he would take a pencil and write to Ann Anna, or Gama on any piece of paper he could find.

And that morning when the shell was lodged in his windpipe and I was trying to get a doctor, Rolf was at the bookcase taking out book after book, and with a pencil marking in some. And all the time he was wheezing and I was trembling at the telephone. At least I got a doctor. Not the one I wanted, but I told him to come immediately. When he came the wheezing was not so heavy.

The doctor put a thin stick wrapped at the end with cotton into Rolf's throat, and forced up a little mucous, and told me not to worry, that now Rolf would be all right.

I remarked that Rolf still wheezed a little, but the doctor quieted my fears and waited while I went for my purse. I asked him his fee, and when he said two dollars, gave it to him and thanked him, and told him I was glad he had come, because he had put my fears at rest.

The doctor walked down the steps to his automobile and rode away.

Rolf seemed alright, except that he wheezed a little. But I did not worry, for the doctor had so reassured me, that even when Rudolph came home a little after five I did not tell him what had happened to Rolf. I waited 'til after supper, and then I told Rudolph everything. Rudolph felt hurt that I had not told him sooner, and even felt worried, but I also reassured him, for I told him all the doctor had said.

The next morning Rolf still wheezed, but otherwise showed no ill effects. He still played around with his tongs and shovel and still wrote to Ann Anna and Gama. But before Rudolph had left that morning he said he was going to speak to Dr. Eckstein about it.

I meanwhile had called up Dr. Ranson the Maplewood doctor and complained of Rolf's wheezing. I suggested the possibility of a piece lodging in his windpipe, but the doctor ignored the suggestion, and said even if there was a piece, it was so small it would not hurt him. And told me to wait a day or two, and if he became worse that day to bring Rolf to his office the next morning.

So again I was reassured, and did not feel alarmed.

A few minutes later Rudolph called me up, told me had spoke to Dr. Eckstein about Rolf. And when Dr. Eckstein heard of the wheezing, he urged upon Rudolph the importance of placing Rolf immediately under a specialist's care.

I was to get the 2-31 train to New York at Hoboken. On the train Rolf was his usual self watching everything as we passed by, and pointing out and naming everything that caught his attention.

Now it was a tower and now a chicken, and then a clock would catch his eye. And then a horse and so on and he would name them all to me, and I would assent and question him.

He wanted to get off the seat and walk around the train, but when I told him that little boys would fall if they walked there, he was content to remain in his seat with mother.

We reached Hoboken and there Rudolph awaited us. Rudolph insisted that I have a bite of lunch and then we took the ferry to 23rd St. We got on a cross town car seating Rolf between us, and all the while he seemed his usual self, interested in everything and everyone.

And he was the same on the elevated, but when Rudolph could not sit with us on account of the crowded car, he called for “Father, father.”

At the 59th Street station we got off, walked to Broadway and then to 61st Street to Miss Alston's Hospital [2]. Rolf even walked up the steps holding onto Rudolph's and my hand. We went right to the office. We introduced ourselves to Dr. Yankauer [3] and immediately were taken to a room upstairs, where while I undressed Rolf, Dr. Yankauer questioned me regarding the whole tragedy. I did not know it was a tragedy then. I know it now!

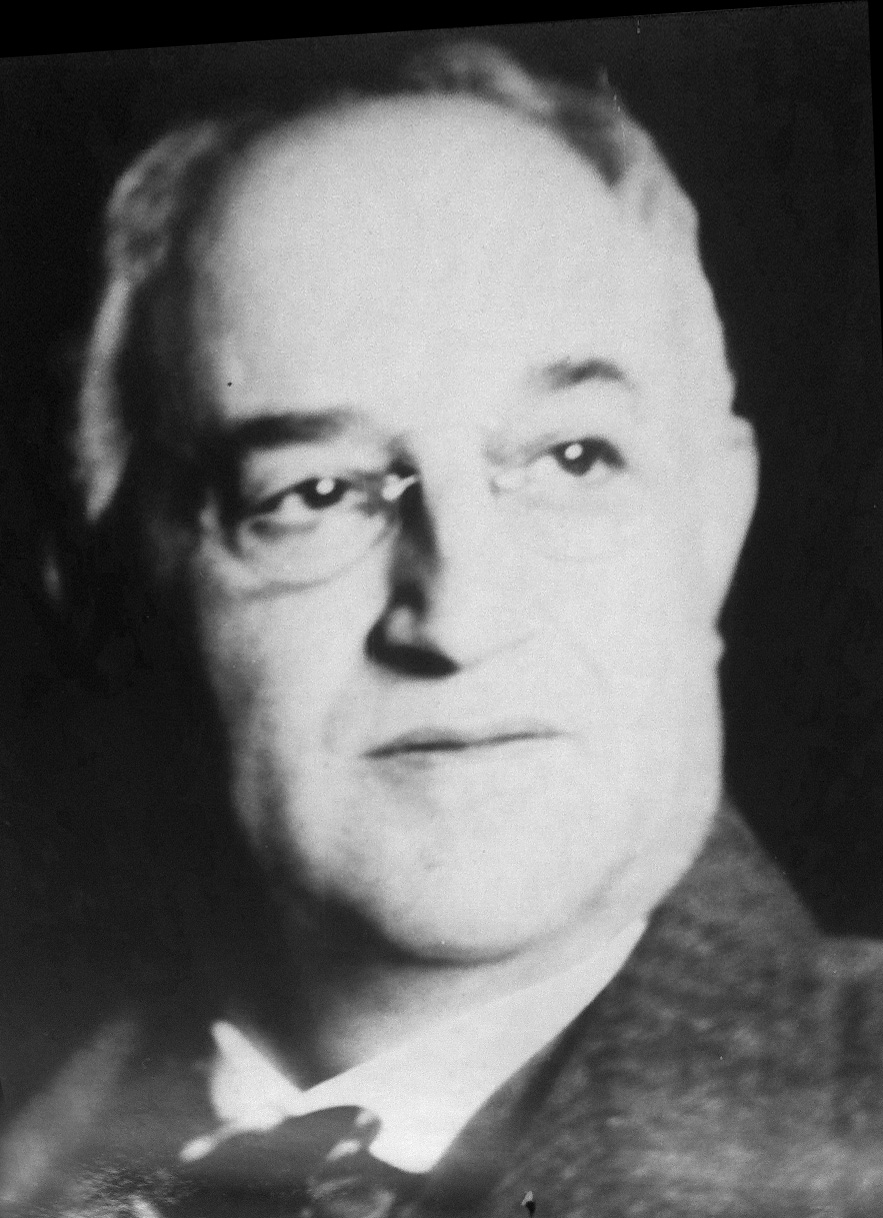

Dr. Sidney Yankauer

Dr. Yankauer examined Rolf, ordered paregoric [4}, which Rolf took willingly, and went out himself to prepare for the “White Party,” as he called it to Rolf.

And still I had no fear. I had been told Rolf would feel ill for a day or two after the operation and would feel better not to be taken home. So I had come prepared to stay a day or two with Rolf at the hospital and then go home.

So I calmed myself as I carried Rolf to the operating room. Rudolph, Miss McPherson, the head nurse, and I with Rolf in my arms went up the elevator to the top floor to the operating room, and then we entered. The doctors were ready, the nurses were ready standing around the sheet-covered padded table, all in their white uniforms.

Ms. McPherson took Rolf from me and told us, Rudolph and I, to go, but I asked to stay. But when Dr. Yankauer asked us to go and said he could only attend to one patient at a time, Rudolph and I sorrowfully went out and stood waiting at the door.

Our hearts were torn as we listened to our little Rolf's cries, as he fought against them all inside the room. For a few minutes all was quiet and then we heard his cries. And then his choking and his wheezing lasted fully half an hour.

I could not go. I had to stay and listen to it all. Rudolph was in agony, but we calmed each other and stood waiting outside the door.

All was still. We heard some whispering inside. The side door was opened and Dr. Yankauer, with the piece of bloody sharp cornered shell stood before us. We cried and thanked him but could say little. But he understood our feelings and told us we could come in.

We went in to the table, and there hot and perspiring lay Rolf. I asked to carry him down, and he was quiet when I had him in my arms, and so well wrapped up. I carried him to the elevator and down to our room and put him in his crib.

Miss Nickerson, the nurse, wrapped him up well, turned the electric current on under the croup kettle, and so Rolf fell asleep for a while.

When he awoke he cried and could only be comforted by my singing the little songs I had always sung to him. My heart was crying but I sang to him and told him to go to sleep. And he reminded me of the pussy cat and the doggie and the bird and Bobbie, and I sang to him of them all. And that quieted him a little, but he was restless and he had that thick croup cough.

Rudolph too soothed him, but he called for mama. So I sat there by his crib, Rudolph taking my place when I went out for a few minutes.

Rolf had been asleep. I had only been gone a few minutes, when Rudolph came running to me. Rolf was crying and asking for me.

We went up to his room and I took Rolf's hand and tried to sooth him by speaking and singing to him. And so I holding his hand, and Miss Nickerson holding his feet - he had wanted me to hold his feet too - he fell asleep again.

Dr. Yankauer had come in to look at Rolf. He said he looked well, had good color, was a little worried about his croupiness, but said we could move him to a better room on the morrow. And then he and Dr. _______ went out and the nurse went out too. And Rudolph spoke with Dr. Yankauer, and told me Rolf was very sick, but there was a good chance for him.

Rolf was quiet, and when the nurse came back Rudolph went out for his supper. I had had mine sent up in the room.

Rolf slept fitfully and would wake up crying, and I had to sing to him to sooth him, and I held his hand so he would know I was near.

Rolf slept again when Rudolph came back, was restless again shortly after, and so was soothed and crying all the while.

Rudolph went out later in the night to get a room in a nearby hotel and left word where we could reach him. But what could Rudolph do all that night more than Miss Nickerson and I? I sang to him all his little songs and spoke to him and held his hands. And once he asked for his wagon and Miss Nickerson put it on his blanket. But he wanted it not for long and I took it away. And Miss Nickerson and I took turns holding the oxygen tube to his nostrils and mouth and Rolf fought the tube away. And we held it so he would not see, and all that night he was in pain. He would cry and would have that rasping wheeze. And every once in a while he would almost lift himself from his crib and throw his chest out and let his head fall back and cry and call mama, that I knew he suffered a terrible pain.

And I asked the nurse, but she said all the croupy babies went through that stage. So though my heart was breaking, I again sang some little songs.

And little Rolf fell asleep again for a while, and again he awoke with a start and cried and tossed about, but I soothed him. And when he asked for water the nurse fed him from a spoon and he took the water eagerly spoonful by spoonful, and so drank down a cupful.

And many times during the night he would ask for water and take it eagerly, and would always want more. And then he would call for “potty, potty” and nurse would put the pan under him and take it away after he had urinated.

And so all night he asked for water and for potty, and cried and gasped and wheezed. And off and on Miss Nickerson or I would hold the oxygen to him.

And I hoped so for the morning, for that night struck terror to my heart. For another nurse had come in, in response to Miss Nickerson's call. But nothing could be done but what we all were doing. The croup kettle was kept up almost all the time, and oxygen given him to inhale almost all the time.

I sat at his side all the time 'til he fell into a sleep. And then I stretched myself on the cot, for Miss Nickerson told me to save my strength for what might come.

For five or ten minutes I lay there, when Rolf became restless again and cried and threw himself up. And I had to do my utmost to sooth him.

And I spoke to him again and I sang again. And after we had given him a little water he became quiet again, and fell again into a troubled sleep. And I sat at his side all the time and would hush him when he became restless, and he slept peaceably for a few hours.

And at last from where I sat I could see the reflection of the early purple morning on my white waist, which hung over a chair. I washed my hands and face, dressed myself and combed my hair. And with the morning my hope arose.

When Rolf awoke he was quieter, and we gave him milk, which he took eagerly. And later I gave him my wristwatch to play with, and he was playing with the watch when Rudolph came in. And I told Rudolph of the bad night we had passed through, but had not called him for it was just the way of the case, as the nurse said.

But Rudolph was glad to see Rolf quieter and then told us of his experience in the hotel. He had locked himself in the bathroom and when he wanted to get out he found the lock would not work. He had left his clothes in the bedroom, and there he stood naked trying to think what to do. He thought of the hazardous climbing from bathroom window to the bedroom, but gave that up because he had left his glasses in the bedroom. And I was horrified when he told me his room was near the top of the hotel.

So with his bare foot he had kicked a panel out of the door and reached for the knob on the other side, and so opened the door into the bedroom. He was a little upset and said a few words to the hotel men, but calmed down on his way to the hospital.

And so he told me his story and I shuddered at our averted tragedy, for I knew if he had attempted to climb from window to window without his glasses, Rudolph would have been killed.

But I spoke hopefully of Rolf's improved appearance. And when Dr. Yankauer came a little later he said Rolf could easily be moved to a pleasanter room. So we moved him to a few floors above into a larger lighter, though drafty room. We found out later it was drafty. You see, the hospital had once been a clubhouse.

And Rolf was quiet all morning, and played with my watch. And we gave him some ice cream, which he ate eagerly. And later he had a little milk, which he also took well.

And he slept for short periods, but as I listened to his wheezing I did not feel easy. And Rudolph stayed with us almost all day, with the exception of going out to his meals. I had mine in the room. Miss Nickerson went down to the dining room.

About 7:00 the doctors came in and were also troubled about his breathing, but could do nothing, just wait and wait, and so went out and left us to our misery.

And later Rolf became more restless and cried, and his inspiration seemed to go down, down, down with that cutting, wheezing breathing. And we became alarmed and asked the nurse to send for the doctor. And after waiting a while and seeing Rolf become more restless and his wheeze deeper and deeper, Miss Nickerson went out to call the doctor.

Dr. Yankauer came, looked at Rolf, listened to him, and I saw by his face that nothing could be done but wait. He ordered paregoric at intervals and to continue the oxygen we had been giving, and stayed a while, and then went out. And Rudolph went out with him and later arranged for a room in the hospital.

And that night little Rolf fought and tossed and cried about. And when he saw Miss Nickerson's cap he became almost frantic. And I begged Miss Nickerson to please remove her cap, for Rolf was frightened at the sight of it. And she removed it for a moment and then put it back, for she said she could not work without her uniform. And later I begged her again, and she kept it off and on at intervals.

And I tried to soothe Rolf by talking to him and singing, but he must have been suffering and nothing could quiet him. And he wheezed and tossed about and I asked the nurse if I could take him in my arms. And when I took him up and held him close to me he became quiet. He must have remembered that somewhere, sometime, someone who loved him had held him so before, and he became restful in my arms. And holding him so, I fed him spoonful by spoonful of milk and he took each spoonful as I gave it to him, and offered no resistance.

And meanwhile, Miss Nickerson made up his crib and the night nurse watched me as I gave him the milk. And when his crib was ready I laid him in and he fell into a sleep. And the nurse asked me to take a little nap on the couch myself. And I threw myself down, for a few minutes it seemed, for at the slightest stirring of Rolf, I was up and at his side.

Later the night nurse brought me a cup of black coffee and a piece of buttered toast. I could not touch the toast, but I gulped down the coffee.

Rolf was suffering all night, and the paregoric we gave him did not quiet him as we wished. And so he tossed about and cried and asked for the potty. And when we gave it to him he would not use it. And we continued giving him the oxygen and at intervals he slept and so on through the night 'til the morning.

And in the morning he was exhausted. And when I took him up in my arms while Miss Nickerson made up his crib, he suddenly assumed a bluish pallor. And the nurse was anxious and called another nurse in and we gave him more oxygen and put him back into the crib, but the bluish color came and went. The tip of his nose was blue and his lips were bluish, and his cheeks had lost all their healthy color. There was no sign now of the little red rash he had had on his face. The rash had gone, gone with some of his life blood, and I tried to still all the fears within my heart.

When Dr. Lewis came in to see him, she looked at him and noticed immediately that the rash had gone. And she spoke to me about it and I questioned myself sadly way down in my heart. Yes, the rash is gone, but my child is going too! I went outside the door with her to the elevator and I told her about the shell. I cried when I told her, but the elevator came up and she said goodbye. But I held onto every hope offered by anyone.

And when Dr. Yankauer came in with Dr. Eckstein later in the morning, and Miss Bowe, the day nurse, the nurse who was breaking my heart with her perpetual smile, smiling while my child was dying, told the doctor about Rolf not having had any movement of the bowels, the doctor spoke in an ordinary way of laxatives they gave children, and asked me what I gave. And I told them I generally waited a day later with good results. But if after waiting there was still no movement I gave Rolf an injection.

They continued speaking for a while in general topics and Dr. Yankauer examined Rolf, asked what nourishment he had had, said to give him more milk and some ice cream and said an injection could be given him later, to continue the oxygen, and the doctors went out.

Later Dr. Eckstein came back and spoke to me about Rolf, that he was very sick but there was a good chance for him. Of course, he said, you could never tell. Babies who were worse pulled through and there was every cause for hope here. And then he told me to try and rest up, but I told him I had to be at Rolf's side, for I was well and I would do everything for my sick child. I was strong and could stand a few sleepless nights if I could save my baby in any way. He did not urge me further and went out.

Rudolph had come in to see us in the morning, but he had been told to stay out of the room, for Rolf needed all the oxygen he could get. And so Rudolph came and went and we tried to cheer each other and we did not give up hope.

And that Sunday on the 18th day of March, the wind whistled and blew in through every crack. And then there was a flurry of snow, a small blizzard in force. And Rolf lay tossing and gasping, and at times he grew frantic. And when I tried to quiet him he would fight me away. He knew me no more and he would slap at me and cry and throw himself about. And then the nurse gave him some paregoric, but he fought that away, too. And when we did succeed in making him swallow it, it did not have the quieting effect, for he still tossed and cried and gasped and fought.

And Miss Bowe the nurse was ready to give Rolf the injection for his bowels, but I asked her to wait a few minutes 'til he quieted a bit, for he did not like to have the enema tube inserted. And asked her again to wait a few minutes, for she surely would not aggravate him now when he fought and cried and threw himself about.

But no, she said she would not wait. She would not bother again getting the enema ready and she would give it to him right now. The doctor said he was to have an enema and he would get it right now, and she was taking care of the case.

But I told her that three minutes or so would make no difference, and as I was there too and saw my child so frantic, I could not allow it, not 'til he quieted down. I did not argue with her. I told her this in a low tone, for I saw my child sinking away.

He did not know me now and when we gave him food to drink he bit the spoon. He wanted air, he was suffocating.

Dr. Yankauer came in, looked at Rolf struggling for his life and himself held the oxygen tube to his face for a while.

Dr. Yankauer, seeing the snow, said something about fickle nature. I could hardly speak; “Yes, fickle life,” I said. I saw my child gasp, gasp for air and nothing could be done. I was helpless. I left everything to the doctor; could do nothing.

We tried to give Rolf some milk while the doctor was there, but he bit the spoon and gasped and tried to bite his fingers, and could not wait for the next spoonful, he was so frantic for air.

And when the doctor went out Rudolph went with him. We continued giving Rolf oxygen, and exhausted he was quiet for short periods.

And while Rolf was quiet I thought I heard Rudolph crying somewhere in the hall, and I was frightened and went to the door to listen. I heard him plainly now, but I myself could not cry. I went back to the crib and sat down by Rolf's side.

And as I looked at him my heart went sinking, sinking, for was this my child, this bluish, yellow, gasping, struggling child. And when he cried I tried to soothe him and Rudolph came in. His eyes were red with crying and I asked him why he cried. He told me what the doctor has said to him, that Rolf was in a most critical condition, but there was still one chance for him and that was another operation, inserting the silver tube into the bronchial tube. The doctor had spoken plainly to him; it was just a last resort.

Rolf stirred and cried and I tried to soothe him and sang to him. And Rudolph asked me why I sang and then I cried. But I cried softly and I took Rudolph's hand and so we stood there at Rolf's side.

And Miss Bowe the nurse came in with the funnel and the tube for the enema. Rudolph held the funnel while Miss Bowe inserted the tube in Rolf's rectum. But no more fighting this time, no tossing or crying about. Rolf lay quiet when the tube was inserted, almost unconscious to his surroundings. He just lay there gasping quietly and I held the oxygen to his nostrils.

He ejected a few little hard lumps with some water, and then we covered him up and tried to put him to sleep. But we all saw that he was slipping and gasping away from us. And we told Miss Bowe to call up the doctor, which she did without argument.

When she came back she said they were getting the operating room ready, and the head nurse would let us know when to bring Rolf up.

The head nurse came in and I took Rolf, little gasping, dying Rolf in my arms, and Rudolph, the nurses and I, with my dying child, went up in the elevator to the operating room. And I put my baby into the doctor's arms, and Rudolph and I, broken hearted, went downstairs to our room.

The room was being washed up by a negro porter, over whom commanded the sharp domineering head of the cleaning force. She had commanded us out of the room, but we did not like her looks or words and stayed.

Frank came up to our room and stayed with us for a while, and then we left him alone while we went to wait outside the operating room.

We did not have long to wait, for soon the doctor called us in and let us look again at our child. There he lay on his back on the operating table gazing up at the skylights, his golden hair falling back from his forehead in soft waves, a little pink tinge in his cheeks and his eyes trying to speak out to us. He was again our child as we had known him, only with a little silver tube in his throat, though now he looked beautiful. And he seemed so far away with that open look in his eyes.

I only took the doctor's hand and thanked him for brining my baby back to life. I could not say very much. “Doctor,” I said, “you can have all the money we have in the bank,” and he laughed and said something about promises.

And we thanked his assistant and all the nurses, and I stood in front of Rolf and saw his lips move with the word “mama,” and I kissed him lightly, reverently on the forehead. And when I spoke to him at the doctor's suggestion and called his name, he seemed to understand. And when he heard Rudolph's voice he moved his lips to fadyer.

But we said no more to him. I sat down on a stool at his side and saw my baby again and hope revived within me. It would mean a hard struggle, the doctor had said, and a long one and we should all work together, and I promised to do all I was told.

So I sat there at Rolf's side and spoke a little to the nurse. And so I sat there on the stool. I saw a shiver pass over Rolf's body and he seemed a little blue. And when I remarked about it to the nurse she made light of it and said they all did it.

And after an hour when the other nurse came back from her supper and this nurse went down for hers I again noticed a shiver pass over Rolf's body and he again looked blue. And I told the nurse and she took his temperature and gave him an injection of strychnine. And then she cleaned his bronchial tube with the electric tube cleaner, gave him another injection of another drug and then sat and waited for the other nurse to come up to help her move Rolf to his room.

And I sat there and looked at my Rolf and once in a while spoke to the nurse. And Rudolph came in again. He had been down with Anna and Dr. Eckstein looking for goose feathers to clean Rolf's tube with. And we sat and waited at his side and then the other nurse came in. It was 7:00. Rudolph took the electric cleaner and a few bottles. Miss Bowe carried Rolf and the other nurse and I carried a few other needed articles.

We went into the elevator and I was alarmed when I looked at Rolf. He was turning blue. “Miss Bowe,” I said, “Rolf is blue and his head is beginning to droop.” She quickly held him low in her arms instead of upright. And when we reached the room I hurriedly pulled back the blankets and Miss Bowe put him down in the crib and took his temperature. When I asked her what it was, she smilingly told me 108. I was alarmed and went down to Rudolph who was with Dr. Eckstein down in the reception room.

As I went out the head nurse came in and was told about the high temperature. I spoke to Rudolph and Dr. Eckstein and silently went back to Rolf's room. There the nurse, upon Dr. Eckstein's inquiry, smilingly told him of another rise in temperature to 110. Dr. Eckstein ordered an injection and asked the head nurse to send for Dr. Yankauer. Miss Nickerson the night nurse just came in. Dr. Yankauer came and ordered hot water immediately. Cloths were put into the water, Rolf's little nightgown split open across his chest and the hot cloths applied, and after a while his temperature taken again. But I saw without looking at the doctors that death was near, Rolf was dying. His upper lip was drawn back from his teeth, his eyes were taking on that fixed stare and his chest rose and shook with his last breaths. They were like dry sobs coming up as a relief after a bitter cry.

And as I looked at him with the silver tube at his throat, it seemed to me that he was in two parts. One part below the neck and the other part the head, only held together by the silver tube.

And as I saw him breathe his last breaths, first his chest rising and then suddenly his head moving a little to a side, it appeared more so to me that he was disconnected. And I said to myself, “How can he live with his head and body separated?”

And we waited around my Rolf, the doctor, the nurse and Rudolph and I, and silently watched him dying. Though the nurse was still applying cloths, we all knew Rolf was dying just one little gasp after another and one little heave after another, and always that little after shake of his head.

The doctors went out, and Rudolph and I stood looking at Rolf, stood watching him, so far away from us and dying, dying.

When I saw my Rolf lying there so, such a terrible change to our Rolf we had brought three days ago, I could not help blaming myself for this terrible tragedy. I looked at Rolf dying and muttered, “I killed him, I killed him.” Rudolph was unstrung and made me promise never to repeat those words.

And then the doctors came in and told us that our child was dying, as though we needed to be told! And told us it would be best to leave him so while he was quiet, as they feared he would have convulsions later on.

I feel so sorry now I was persuaded to leave the room; they said it would be best for me. I could not stand the strain. And going to my Rolf, the little that was left of Rolf, I stroked his silky hair away from his forehead and said to myself, “Is this the end? Oh, how could this be” and kissed him on the forehead reverently, as I had kissed him before. And then I stood and looked at him a little while and slowly walked to the door where Rudolph was standing waiting for me.

We went downstairs to the reception room and sat down on a couch, and then realized the misery that had entered our lives. We cried and spoke to each other sadly of our loneliness.

And then Miss Bowe the nurse came over and expressed her sympathy, and Rudolph could not abstain from telling her she could have shown more sympathy with us if she had restrained her smile occasionally. “Well,” she said, “we nurses in our profession must have a smiling face. We can't go around looking gloomy.” No, we did not ask her to look gloomy. All we asked was when we in our misery were suffering, just a little comprehension of a tragedy, and not flaunt that smile.

So she left us and we sat for a while and then we went upstairs. As I entered the room and looked at the crib I saw that my child was still breathing. The doctors were sitting around and the nurse was holding a thermometer. “Doctor,” I said, “is there still a chance,” but I needed no reply.

We had our last look of living Rolf. He was still giving a little gasp. I kissed my baby but I felt I was kissing a lifeless corpse. And I pushed back his hair from his forehead and gazed and gazed.

And then Rudolph and I went out into the night, but we were so alone. People walked near us but we seemed so far from all. We walked a while but could not stay out long, and sorrowfully we went back to the hospital to the reception room where we sat down to think of our calamity. And we sat there thinking, going over oh so many things that had happened. And we sat there not speaking to each other.

So we sat when the doctors came down. Our little boy had fought hard but the odds were against him. And so quietly, just one gasp after another he breathed his last.

They felt for us and tried to cheer us and Dr. Yankauer filled out the death certificate. Anna came in with goose feathers, goose feathers which were to clean Rolf's tube. She had been all over town to get them and had at last succeeded. Goose feathers which little Rolf needed no more. We told her. The tears came to her eyes. She was very sad but she helped us all she could. She told Rudolph where to telephone for the cremating of Rolf's body, and helped us to bear up. And Dr. Eckstein was also very good to us.

Later Anna went with us to help us pack our few things. And as we entered the room where Rolf lay dead, the nurse was just putting the final touch to his death makeup. Nothing seemed to matter anymore. Mechanically I packed up Rolf's clothes, Anna and Rudolph helping. But through it all I saw Rolf's sad, sad look asking, “Why, why?” Whenever I had asked him why he had done a certain thing, he would always answer, “Why, why.” His look cut me through and through, not accusing but merely looking sad, so sad.

Everything was packed. We had little. I had been told we would only have a short stay of a day or two before we came. We took one last look at little Rolf. Little Rolf now rid of all his sufferings. How quietly he lay there. No gasping, no crying, but his eyes spoke to me, even those dead eyes fixed by the nurse. I saw the sad reproach there and I let it sink into my heart as I stood looking at him. And then we said goodbye to the nurse and waited for the elevator to take us out.

We felt sad and lonely as we walked out of the hospital and we knew we had seen the last of our child. What a change had come over. How dark and cold everything seemed to be.

We passed a restaurant and we went in for a cup of cocoa. I drank it slowly, thinking, thinking all the time. Then we took the elevated train and went home with Anna.

REFERENCES

1. (John) Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 - March 6, 1941) was an American sculptor famous for creating the monument to the presidents at Mt. Rushmore, in South Dakota.

2. Miss Alston's Hospital (AKA Miss Alston's House for Private Patients) was a private hospital at 26 West 61st Street in New York City (previously at 143 West 47th street). This text is from an advertisement:

3. Sidney Yankeuer, MD (1872-1932) was a well known otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist) in New York City. While mainly remembered today for the suction device that he designed, he was also a leader in the early days of endoscopic airway management.

Miss A. L. ALSTON, for nearly eight years Superintendent of Mount Sinai Training School for Nurses, opened, September, 1894, a house for the reception of private patients.

Miss ALSTON'S long and thorough experience will insure the best of nursing and general supervision for those who are in her charge. Great attention is paid to the careful and appetizing preparation and serving of the food.

All classes of cases, male and female (including maternity cases), will be received, excepting those suffering from contagious diseases or mental disturbances.

The house will be open to the patients of any reputable physician, and will remain entirely in his charge, no house officer being in attendance.

4. Paregoric is a narcotic drug, a derivative of opium, which was used in the 19th and early 20th centuries to control diarrhea, as an expectorant and cough suppressant, and to calm children.